Archaeology in the Nile Valley: Egypt-Sudan

The Swiss-French-Sudanese archaeological mission at Kerma – Dukki Gel

Swiss grants

- The State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation SERI, via the Kerma Foundation

- Private donations

French grants

- Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères MEAE

- Sorbonne University, UMR 8167 Orient & Méditerranée

- Nile’s Earth, ANR-21-CE27-0019-01

The Swiss-French-Sudanese archaeological mission at Kerma – Dukki Gel is co-directed by Xavier Droux, Séverine Marchi, and Abd el-Hay Abd el-Sawy. It follows on from the pioneering work carried out in Tabo under the auspices of the University of Geneva and the direction of Charles Maystre from 1965 onwards. Fieldwork was first directed by Jean Jaquet and, from the second season onwards, by Charles Bonnet. Professor Bonnet assumed the overall direction of the expedition a decade later, shifting the focus of the excavation over to the ancient city of Kerma.

The Swiss Archaeological Mission at Kerma was established in 2002; it is today divided into two vast and distinct concessions: the necropolis and desert sites are under the responsibility of the mission of the University of Neuchâtel, headed by Matthieu Honegger, while the two urban sites of Kerma and Doukki Gel are studied by the mission affiliated to the ARCAN Laboratory since 2022, with the support of the State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation, the Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, and the UMR 8167-Orient & Méditerranée (CNRS, Sorbonne University). In Sudan, the mission works in close collaboration with the National Corporation for Antiquities and Museums as well as the Swiss and French diplomatic agencies in the country.

The ancient city of Kerma, capital of the eponymous kingdom, has revealed the remains of dense occupation that dates to as far back as the middle of the 3rd millennium BC. Residential areas and administrative buildings developed around an imposing religious quarter dominated by the main temple, the Deffufa. Excavations have revealed original architectural features and sometimes unique craftmanship. The archaeological data collected at Kerma reflects the wealth and dynamism of a community that thrived at the heart of a powerful and vast kingdom.

To the north of the ancient city lies Dukki Gel, where the mission has been focusing its activities since the early 2000s. The chief interest of this site lies in its preserved mud-brick architecture. Often levelled to the ground, the buildings were erected using local styles, techniques, and technologies – with a clear preference for rounded floor plans – in contrast to the more usual quadrangular Egyptian monuments. This site is far from having revealed all its secrets: it was occupied for several millennia, and its preserved surface covers an area of over seven hectares.

One of the most significant discoveries made at Dukki Gel is a series of seven monumental statues, broken up and buried in a pit dug within the Kushite-period religious complex: dating from the 7th-6th centuries BC, they represent five rulers from the end of the XXVth dynasty and the Napatan period: Taharqa, Tanutamun (two statues), Anlamani, Senkamanisken (two statues) and Aspelta.

This long-running work on two sites of major importance in the Nile Valley continues to reveal fascinating clues about the Nubian regional context as well as Egypt and Central Africa and is reconnecting local populations with the treasures of a little-known history.

STORinJAR

Le projet FNS STORinJAR TMPFP1_217261. Storing food in Ceramics. Multiscalar and interdisciplinary analysis of storage jars used in the lower Nile Valley (Egypt and Sudan) during the Early and Middle Bronze Age – Adeline Bats

2023-2025: https://data.snf.ch/grants/grant/217261

Food storage is a central theme in the study of ancient civilisations, since it enables us to understand the strategies implemented by different societies to guarantee food security for their populations, as well as the different uses to which surpluses were put.

From the 1980s onwards, this area of research developed considerably in protohistoric, ancient and medieval Europe, under the impetus of François Sigaut, who took a particular interest in the conditions created by human beings - throughout history and in different societies - to ensure the proper preservation of perishable foodstuffs.1 . In the case of the Nile Valley, the question of food storage was rarely raised directly and was dealt with on an ad hoc basis, based on iconographic data.2 , textual or archaeological. However, this research is mainly aimed at estimating the quantities of cereals conserved, or at the social organisation of stock management.3 .

Other research has also been carried out on an ad hoc basis, as archaeological discoveries have come to light.4 . They are based above all on a certain reading of the iconography, with the aim of proposing a functional analysis of the buildings. However, all these contributions have neglected an essential aspect of storage: the technical aspects, and in particular the atmospheres in which the products were kept. The terms "granary" and "silo" - often regarded as synonyms - are mixed indiscriminately, ignoring the specific characteristics of the foodstuffs stored and suggesting economic and social interpretations that are sometimes debatable.

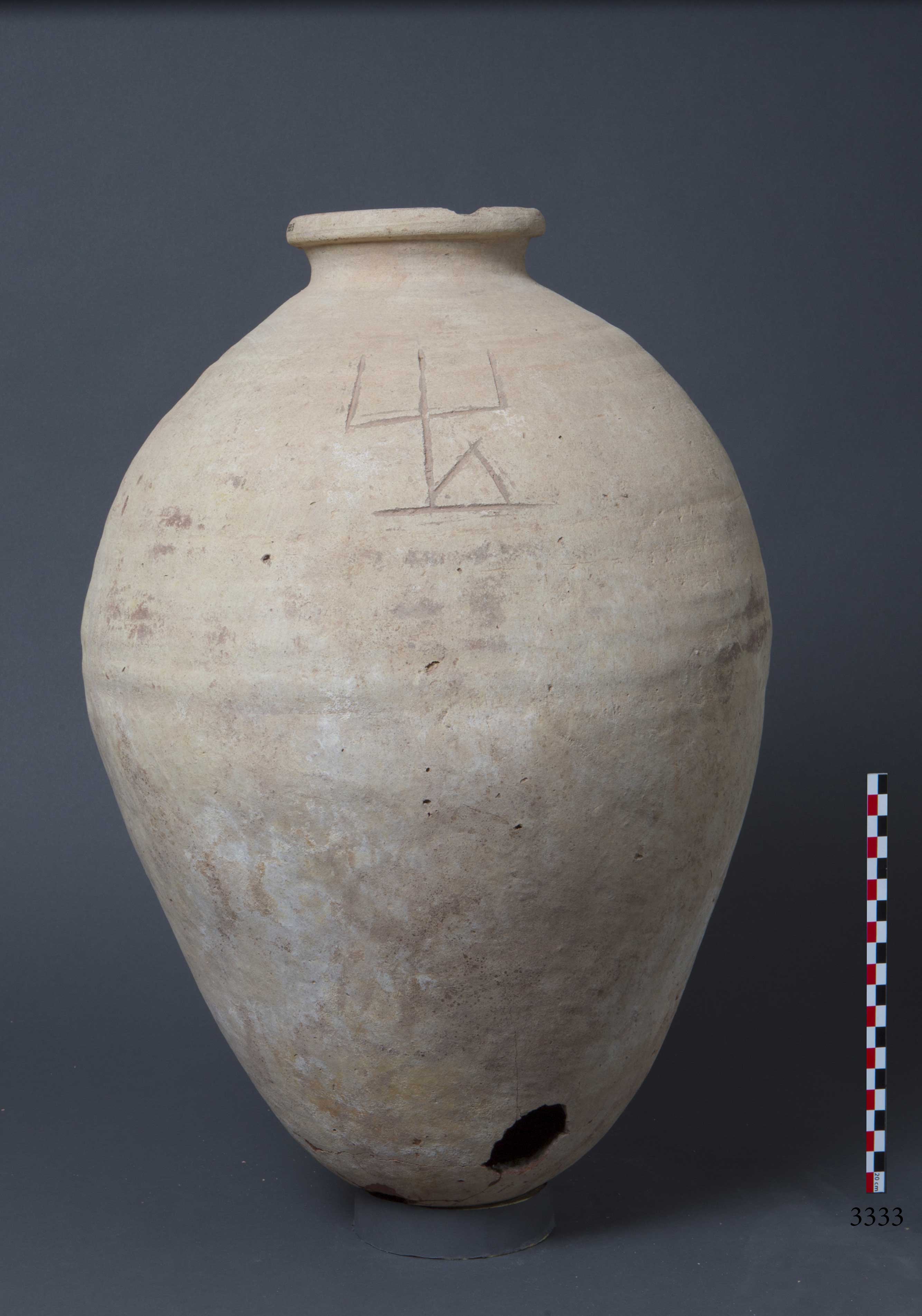

With silos built in mud brick5 , storage ceramics are the most common type in Egypt and Nubia. To date, this material is mainly known from typo-chronologies, although some functional analyses have been initiated.6 . My aim is therefore to propose a study of the anthropic phenomenon of storage in jars in the northern Nile valley, based on all the available sources, in order to determine the variables and invariables in the use of these containers, which may have been used for domestic storage or the exchange of foodstuffs.

To carry out this research, I have access to a number of previously unpublished collections, such as the jars discovered at Ayn Soukhna (Sorbonne University/IFAO), those from the gallery-stores at Ouadi el-Jarf (Sorbonne University/IFAO), and the Egyptian and Sudanese jars from the Kerma Doukki-Gel site (University of Geneva / Sorbonne University), some of which are held at the Geneva Museum of Art and History.

These ceramics will be studied according to the principles of techno-functional analysis, as has already been done for material from other civilisations.

The aim is to distinguish the macro-traces left by the potters from the stigmata testifying to the uses to which the ceramics were put. Traces of shaping, as well as petrographic analyses, will help us to better understand the technical choices made by potters in the production of containers capable of preserving and transporting raw or processed foodstuffs or liquids.

These unpublished bodies of work should be considered as 'case studies' to be compared with other textual and iconographic data, as well as with previously published jars that provide relevant contexts for technical and functional analysis. The petrographic analyses will be carried out by Mary F. Ownby (University of Arizona). Analyses of food residues will also be carried out in collaboration with Martine Regert (UMR 7264, CEPAM) on Sudanese material. These analyses focus on organic and lipid residues in order to determine the types of plants or lipid-rich foods (such as meat and fish, animal fat and beehive products) that were stored there.

This research will be supplemented by experiments carried out in partnership with players in the organic farming and food sector, and by analysis of the experimental samples by Jean-Michel Savoie (INRAE-Bordeaux), to determine whether the grains are still consumable - for food and germination - after storage in the experimental jars. This will also enable hypotheses to be put forward on the storage of seeds, which are particularly valuable assets for farmers as they are carefully selected from the cereal stock.

Egyptian texts - mainly delivery notes - will provide information on the products stored, the types of containers and the transport of goods, while iconography will provide data on uses (storage, transport).

Archaeology will provide information on the creation and use of the jars, based on macro-traces and the contexts in which they were found. Analysis of the residues will provide additional information on the contents of the jars, in addition to the textual sources.

Finally, experimentation will make it possible to test hypotheses and question sources more closely throughout the research process. Analyses of the experimental grains will make it possible to validate or invalidate the protocols and provide results on the viability of ancient Egyptian and Nubian storage methods. In addition, ethnographic comparisons will make it possible to define variables, trends and invariables in the use of jars by a given human population. The synthesis and analysis of the information gathered will be based on techno-economics, seeking to define the elements specific to specific uses and anthropological invariables.

- Fr. SIGAUT, Les réserves de grains à long terme – Techniques de conservation et fonctions sociales dans l’histoire, Paris, 1978 ; M. GAST, Fr. SIGAUT et al. (éd.), Les techniques de conservation des grains à long terme, leurs rôles dans la dynamique des systèmes de culture et des sociétés, 3 volumes, Paris, 1979-1985.

- R. SIEBELS, « Representations of granaries in Old Kingdom tombs », BACE 12, 2001, p. 85-99 ; M. BARDONOVÁ, « Grain storage in the Old Kingdom. Relation between an object and its image », dans K.O. Kuraszkiewcz, E. Kopp, D. Takács (éd.), ‘The perfection that endures…’ Studies on Old Kingdom Art and Archaeology, Varsovie, 2018, p. 43-60.

- B.J. KEMP, « Large Middle Kingdom Granary Buildings (and the Archaeology of Administration) », ZÄS 113, 1986, p. 120-136 ; L.A. WARDEN, « Grain as wealth in Egypt: Field – silos – bread and beer », dans A. Bats (éd.), Les céréales dans le monde antique. Regards croisés sur les stratégies de gestion des cultures, de leur stockage et de leurs modes de consommation, NeHeT 5, Paris, 2017, p. 141-156.

- M.D. ADAMS, « Household Silo, Granary Models, and Domestic Economy in Ancient Egypt », dans Z.A. Hawass, J. Richards (éd.), The Archaeology and Art of Ancient Egypt. Essays in Honor of David B. O’Connor, vol. I, CASAE 36, Le Caire, 2007, p. 1-23.

- A. Bats, N. Licitra, T. Joffroy, B. Lamouroux, A. Feuillas, J. Depaux, « The Egyptian mud-brick silo. Technical and functional analysis of a grain storage device », dans A. Bats, N. Licitra (éd.), Storage in ancient Egypt and Sudan. I. Earthen architecture and buildings techniques, Actes des deux journées d’Étude du Groupe de Travail (2020 et 2021), Leyde : SidestonePress, 2023.

- T. RZEUSKA, « Grain, Water and Wine. Remarks on the Marl A3 transport-storage Jars from Middle Kingdom Elephantine », CCE 9, 2007, p. 461-530.

Ponda

The Ponda.org platform is an online tool for the scientific community and the wider public, focusing on artefacts from predynastic Egypt dating to the fourth millennium BC. Xavier Droux, external collaborator, initiated this large-scale project and is its current editor; he works in close collaboration with several researchers specialised in predynastic Egypt. The platform primarily aims to associate these objects with their origin, current location in museums and collections, and relevant literature.

The platform consists of interconnected databases for artifacts, individuals (archaeologists, collectors), archaeological sites, collections, and publications. It facilitates collaboration and understanding of ancient Egyptian artifacts, promoting cultural heritage exploration.

The development of this project is supported by the Thomas Heagy Foundation.